How Georgia’s Gold Rush Began 1828–1838

Thar’s Gold in Them Thar Hills

In the late 1820s the ridges and creeks of what would become Lumpkin and White counties were still within the Cherokee Nation. Rumors of bright metal in the gravels had circulated for years, but in 1828–29 scattered finds turned into a stampede. By the end of 1829 thousands of prospectors—quickly nicknamed “Twenty-Niners”—had poured into north Georgia.

The first sparks: 1828 discoveries and an 1829 newspaper that lit the fuse

Local lore offers several origin stories, but two threads matter most: credible 1828 finds in the Nacoochee Valley and the first widely circulated printed notice in August 1829. The Georgia Historical Society’s marker at Dukes Creek recounts that a North Carolinian named John Witheroods found a three-ounce nugget there in 1828, and that merchants in the valley handled an extraordinary volume of gold in the following decades—evidence that stream placers were paying. Meanwhile, the Georgia Journal (Milledgeville) printed a notice on August 1, 1829 announcing that “two gold mines have just been discovered,” the item that sent hopeful miners south in droves. Taken together, an 1828 trickle and an 1829 media spark explain why the rush crested so suddenly.

Where the rush hit first: Auraria and the Cane Creek diggings

As miners arrived in late 1829 and 1830, the Etowah and Chestatee watersheds and nearby creeks (Yahoola, Cane Creek) filled with camps, rockers, and sluices. The first boomtown was Auraria, founded in 1832, with stores, law offices, and boarding houses packed along muddy streets. A few miles to the north, the Cane Creek area took off as well, and a new town site—Dahlonega—soon eclipsed Auraria. Contemporary and retrospective accounts agree that in the very first years the real money came from easily worked placer deposits in stream and bench gravels.

“Four thousand on Yahoola”: scale and speed

Just how big did the early rush get? One widely quoted metric appeared in Niles’ Register in spring 1830, reporting 4,000 miners on Yahoola Creek alone. Other contemporary numbers are scattershot and sometimes boosterish, but all agree the influx was massive for a thinly settled mountain frontier. Within a year or two, claims dotted the hills from Cherokee County in the southwest to Union and White counties in the northeast, tracking the arc of the Georgia Gold Belt.

From pans to stamp mills: how early miners worked

From pans to stamp mills: how early miners worked

The earliest operations were placer diggings: panning, cradles (“rockers”), long toms, and sluices aimed at heavy gold that settled behind boulders, on inside bends, and on bedrock crevices. As the easy gravels thinned, companies organized to chase the hard-rock (lode) sources—the quartz veins that had shed gold into the streams. By the mid-1830s investors erected stamp mills to crush ore and recover fine gold, and in a few places tried hydraulic methods to wash decomposed bedrock (“saprolite”) off hillsides into sluices—an approach that would later scar ridges like Findley Ridge near Dahlonega. The technical progression—placer first, lode next—is the through-line of nearly every local mine history from these years.

Money, merchants, and mints: turning dust into coin

All that raw gold needed buyers and assayers. Merchants in the Nacoochee and Dahlonega areas handled significant volumes; one tradition recorded on the Dukes Creek marker claims $1–1.5 million purchased and shipped from a single valley merchant over thirty years. Whatever the exact tallies, the trade was robust enough that Georgia sent substantial deposits to the federal mint in Philadelphia by 1830, even as locals clamored for a closer coining facility to reduce losses in shipment and assaying discounts. These arguments—plus gold in neighboring North Carolina—persuaded Congress in 1835 to authorize branch mints in Dahlonega, Charlotte, and New Orleans.

Town-building amid turbulence

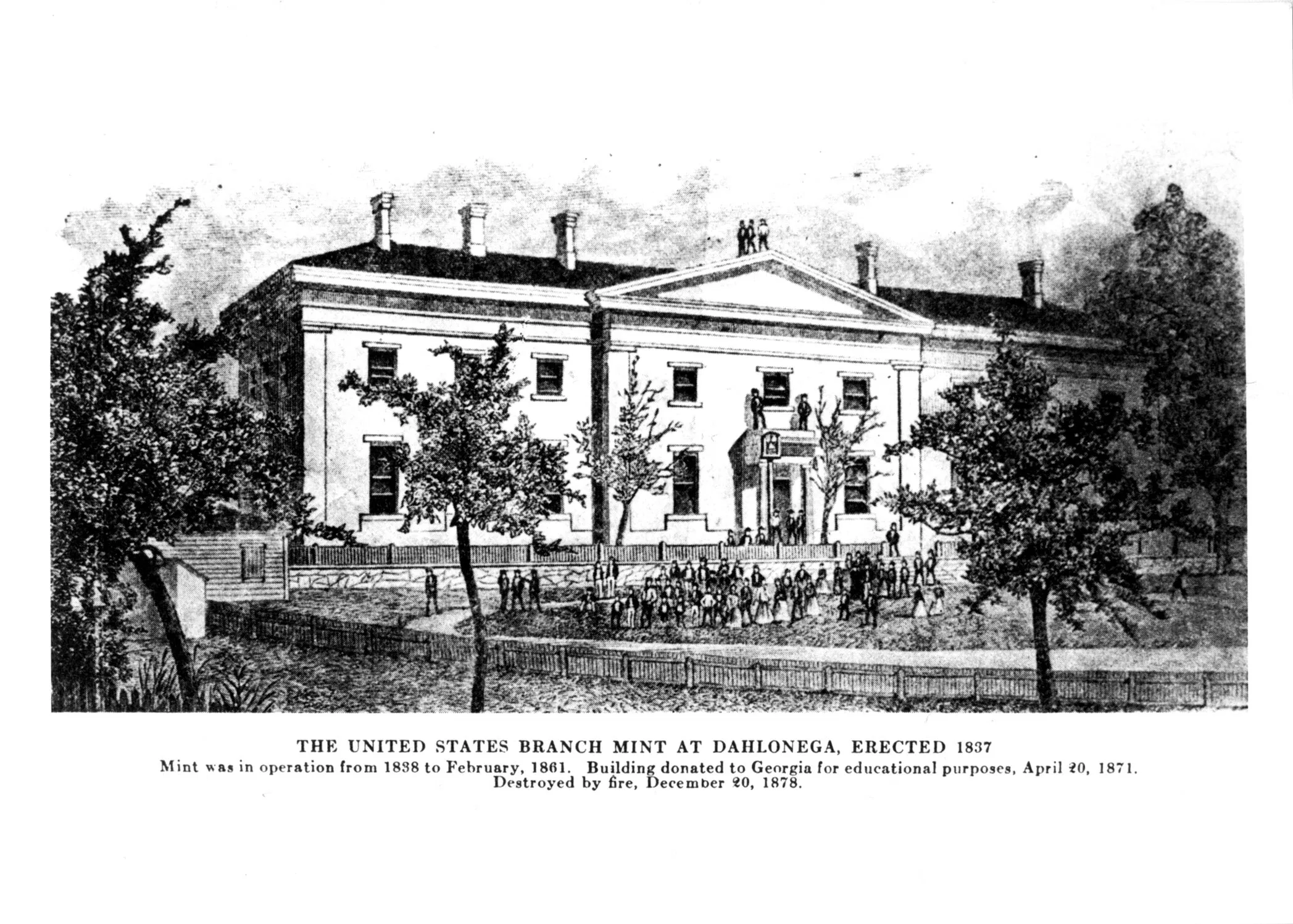

While new ditches, roads, and mills crisscrossed the hills, the legal regime on the ground shifted rapidly. The 1832 land lottery parceled out much of the gold country to Georgia citizens, fueling speculation and frequent resale, while earlier Cherokee claimants and miners faced mounting displacement. In the midst of this, Dahlonega was surveyed and established, steadily taking civic primacy from Auraria. That the U.S. chose Dahlonega for a federal mint—approved in 1835 and opened February 1838—signaled recognition that this was the commercial and administrative hub of Georgia’s gold fields.

On the eve of coinage: the first decade’s arc

The first decade of Georgia’s rush thus follows a clear arc:

-

1828: credible early discoveries (notably at Dukes Creek) pull experienced hands from Carolina into northeast Georgia.

-

1829: the Georgia Journal’s August 1 notice flips rumor into a full-blown rush; thousands arrive that autumn and winter.

-

1830–31: placers boom; reports like Niles’ Register tally thousands at single creeks; fights over authority and access intensify on Cherokee land.

-

1832: Georgia’s land lottery in the gold counties accelerates Euro-American settlement; Auraria peaks while Dahlonega rises.

-

Mid-1830s: capitalized lode mining and stamp mills gain ground as easy placers wane; Congress authorizes a Dahlonega branch mint (1835).

The Dahlonega Mint opens (1838)

The Dahlonega Mint opens (1838)

Construction proceeded through 1836–37, and the Dahlonega Branch Mint opened in February 1838. The first coinage—$5 half eagles—was struck on April 17, 1838; later years added gold dollars and quarter eagles, and in 1854 a small run of $3 pieces. Ironically, production began just as the richest local placers had faded, but the mint validated a decade of feverish mining by converting local gold into federal coin right in the mountains where it was found.

What the first years left behind

By the time presses clanked at the mint, the landscape had been transformed: creek bars stripped to bedrock, ditches and flumes contouring hillsides, mill foundations thudding beside sluice boxes, and two boomtowns—one fading (Auraria), one ascendant (Dahlonega). The rush also left hard legacies: the dispossession of the Cherokee and a volatile legal transition that shadowed every claim. Yet the decade from 1828 to 1838 fixed Georgia on the national gold map and seeded a mining culture that would echo into later revivals and, for many veterans, an exodus to California in 1849.

In short: Georgia’s gold rush began as creek-bed rumors turned to printed fact in 1829; swelled to thousands working placers by 1830–31; shifted to deeper, capital-intensive lodes mid-decade; and culminated in Congress placing a U.S. mint at Dahlonega, where, on April 17, 1838, the first coins struck from Georgia gold left the coining room and entered American commerce.